Talkback tirades and tabloid beat-ups about battles between drivers and cyclists are a staple of the debate over Sydney’s developing bike lane network; but it’s a completely different story in Melbourne, where even bigger steps to get people riding to work enjoy public and mainstream media support.

In an intriguing tale of two cities, the Victorian capital has quietly emerged as a global leader when it comes embedding bicycle-friendly infrastructure into the fabric of its transport masterplan, just as broadly similar efforts in Sydney remain the target of sustained attacks that decry commuter cycling as a wasteful hipster folly that creates traffic gridlock and puts pedestrians in mortal danger.

(And that’s before recent punitive increases in fines for NSW riders coupled with new requirements to carry photo ID are taken into account.)

So what gives?

Bicycle bipolarity

The bipolar difference in media and public sentiment is now such a phenomenon that urban planners, government officials and policymakers are sitting-up and studying the chasm as cities and towns across Australia grapple with how to promote active lifestyles and deal with deal with traffic congestion.

Almost any bike lane extension in Inner Sydney – proposed or real – is a sure fire candidate for a roasting on morning or drive time radio.

Yet on the 15th March, the City of Melbourne and Lord Mayor Robert Doyle signed-off on the latest four year Bicycle Plan that now aims “to increase bike use to one in four vehicles entering the city in the morning” by 2020.

That’s a quarter of inbound traffic, a target that would likely be laughed off the road by Sydneysiders still struggling to come to terms with separated bike lanes on city streets. In Melbourne the target barely rated a mention.

On the surface, Melbourne’s sweltering summers and cold, often wet winters should to be enough to prompt the average cyclist to think twice about committing to serious two wheeled commuting.

But cyclists are taking to Melbourne’s streets in their droves. The number of cyclists entering Melbourne’s CBD has maintained double digit annual growth and is now estimated by Bicycle Network – Australia’s peak national cycling advocacy body – to be clocking up between 12,000 and 15,000 bikes a day.

Bicycle Network should know too, given the organisation routinely compiles bike counts on cycleways and streets – even if many traffic authorities still don’t collect such data.

Bicycle Network’s chief executive, Craig Richards, acknowledges the stark difference in cultures between the two cities, but argues that mainstream acceptance of cycling as an integral part of commuting in Melbourne has been secured and reinforced in bite size chunks over a long time.

“The transformation of Melbourne into a bike friendly city started many years ago,” says Richards.

“The stages were incremental, not dramatic [and] that policy has been supported by political parties of both persuasions and most local governments and councils.”

While cyclists commuting into Sydney appear to overwhelmingly support the introduction of physically separated bike lanes, that city’s comparatively rapid rollout, coupled with the forced changes and disruption as well as the publicity that has ensued, go a long way to explaining the heat being generated.

In 2008, the City of Sydney committed a whopping $70 million to cycling works over four years. The backlash from increasing frustrated car drivers – not to mention the occasional minister – has been coming ever since.

Part of that frustration stems from Sydney’s street planning (or lack of it) which has been ad hoc since colonisation. The ‘organic’ evolution of the city makes retrofitting of infrastructure like light rail and separate bus and bike lanes not just expensive, but awkward and often crowded when compared to Melbourne’s wide and purposeful grid system of roads.

Down south, it’s been a slower and much quieter battle for cycling hearts and minds and one that’s been burning for decades.

“There’s never been any huge spending announcements in Melbourne, it’s been drip fed,” says Richards. “There’s a 30 year history of encouraging bike riding.”

“Most of the media has come on board [in Melbourne and this] reflects the very large numbers of people riding bikes.

“We know it’s very different in other states.”

Richards credits City of Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore for taking the “early running” on embedding cycling infrastructure into the commuting fabric of the city, but pointedly observes adjoining local government areas also need participate to definitively get things moving.

“It hasn’t really spread through other parts of Sydney,” Richards says. “But councils are slowly responding.”

The Suburb-to-City (dis)connect

The suburb-to-city cycling disconnection that Melbourne has been progressively ironing is now increasingly becoming a big part of its success as a pedal powered city. The solutions are varied, sometimes a compromise, but at their core give riders sufficient demarcated space to feel confident and safe on their journeys.

There is simply less fear of getting clipped by a car, as this video of an incident in front of Government News’ Sydney office illustrates (last 5 seconds).

The nirvana of an urban cycleway for riders is a physically separated, unidirectional lane or path that gets you from home to work (or wherever) in around the same or less time than a car or public transport.

Richards says that as the quality of cycling infrastructure increases, so too do the distances that riders commuting to work are prepared to clock up. That means distances once constrained to around 5km can easily stretch out to 10km and sometimes extend to 15km for the more committed.

If you consider most people working in offices tend to gravitate towards one or more concentrated points, the realistic opportunity of riding opens itself up to more and more people as cycling infrastructure extends.

Corporate employers and property developers are also buying into and backing commuter cycling, and not just to gain a few corporate-social responsibility brownie points.

The City of Melbourne has been getting developers to put cycling and active lifestyle facilities into offices for more than a decade, but Richards says such features are now becoming a staple in Sydney too.

“Big corporate offices have bike parking for 400 to 500 bikes,” Richards says. Of course it doesn’t hurt that every bike potentially either saves a company the cost of a car space or frees one up for a driver that has far fewer transport options.

And while few companies measure it, there’s no disputing the productivity downside that occurs when drivers parked in two-hour zones duck out to check or move their cars, or collectively rush from their desks when a group email about prowling parking inspectors goes around.

Safety the prerequisite for women

Although elements of the media frequently call out risk-taking behaviour by male cyclists on roads and at traffic intersections, the behaviour and perceptions of female cyclists are almost routinely ignored.

Richards says that women place a very high value on the safety of their journey, a factor that in turn directly influences their uptake of riding.

“Physically separated bike lanes are essential to get women riding,” he says, noting that on lower quality bike infrastructure (like painted lanes on roads) female participation tops out at around 25 per cent.

But the female participation rate almost doubles when there is full separation, like a physical buffer on the road or a dedicated off road path, with Richards estimating that female counts rises up to 45 per cent of riders.

“That’s a major priority for Bicycle Network,” Richards says. “In Europe more females ride to work than males.”

“Our surveys show that a large number of people would like to ride to work but don’t because they’re scared of the traffic.”

If drivers prefer the comfort and convenience of their cars to public transport, the same motivation seems to be at least in propelling bike riders. Richards notes that congestion and increasing passenger density on public transport has many commuters looking for a more spacious alternative.

“In the inner city, public transport infrastructure is already crowded,” Richards says.

Council mergers a catalyst for coordinated change

Forced council mergers now sweeping across NSW are generating plenty of grass roots and political heat, but at the end of the day they could also present a once in a generation opportunity for new amalgamated entities to jointly plan much better cycling strategies.

Richards won’t buy into the divisive politics of council amalgamations, but he’s certain a glass-half-full approach to bigger local governments can help overcome fragmented and disparate efforts to encourage riding.

Bicycle Network has been a long-term critic of councils that talk big about sustainable transport but then only invest tokenistic amounts on cycling infrastructure that often only results in bike symbols being painted on bitumen.

In 2012 the group outed Randwick, Botany Bay, North Sydney and Leichardt councils as just some of the local governments that wouldn’t even provide data for Bicycle Networks annual spending survey that year.

With mergers now all but a done deal, Richards is urging stakeholders to come together to find a better way forward.

“The amalgamations will provide an opportunity for a rethink on bike strategy,” Richards says. “[There will be] more opportunities for more collaboration between councils.”

Better coordination between councils within 15km -20km of Sydney’s CBD is shaping up to be a critical issue as Sydneysiders increasingly mount-up to avoid several years of anticipated major traffic disruption caused by major projects that include the construction of a new Metro rapid rail network, the extension of light rail to the east and west and the massive new Westconnex toll road.

One the biggest opportunities already sacrificed by both Labor and Liberal state governments is the construction of so-called ‘Green Way’ that would have provided a separated cycling and pedestrian trunk line that hugged the inner west light rail line and took self-powered commuters into the CBD.

While a partial ‘GreenWay’ corridor has been constructed, for the time being it remains disconnected and isolated – like much of Sydney’s dedicated cycling and pedestrian commuting infrastructure.

Developers recasting the transport landscape

Given the high cost of retrofitting dedicated bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure, it shouldn’t come as a complete surprise that property developers are quickly climbing on the non-car transport bandwagon.

Proximity to high capacity public transport has always yielded a healthy premium, but as urban density becomes tighter and tighter the addition of dedicated cycling infrastructure is also becoming a must have for big infill projects such as Sydney’s Green Square redevelopment.

Developers of course see a win-win scenario in replacing cars with bikes: authorisation to build blocks of units with a minimum or of dedicated off-street parking spaces can produce a far more lucrative yield because developments are not constrained by the number of car spaces.

Sydney Lord Mayor Clover Moore is conspicuously talking-up the rare opportunity to put greenfields infrastructure into the central city area.

“The cycleways through Green Square will give local residents and businesses an easy, comfortable and safe 15 minute ride to Central Station, with the capacity to transport more than 50 busloads of people a day,” Moore says.

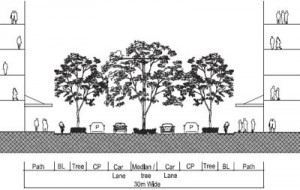

“Planning Green Square from the ground up has given us a unique opportunity to create a 36-metre wide central spine through the Green Square Town Centre – wide enough to accommodate a one-way separated cycleway on both sides. This is a first for Sydney, as all our other cycleways are retrofitted on narrower streets.”

Wide streets and planned transport infrastructure… maybe not such a first for Melbourne, but at least things are moving.

Great article, and mostly agree. So let’s pick nits – cyclist advocates’ favourite activity!

[“The stages were incremental, not dramatic … that city’s comparatively rapid rollout, coupled with the forced changes and disruption a…go a long way to explaining the heat being generated.”]

In Netherlands and Denmark they have been working on it for 45 years. But at a much faster and comprehensive rate than Melbourne.

In New York, they did a lot fast. Yes there was bikelash, but it also gets lot’s of people on bikes (and pedestrians) numbers up fast. cf http://www.amazon.com/Streetfight-Handbook-Revolution-Janette-Sadik-Khan/dp/0525429840

[“The ‘organic’ evolution of the city makes retrofitting of infrastructure like light rail…”]

ooohh you gotta learn a little local history. Up until the late 1950s Sydney’s light rail system was much more extensive than Melbourne’s even today. It was huge and hugely successful. It was pulled out “to reduce congestion”. That didn’t work out very well for Sydney, did it? Nonetheless, I do agree your “heritage” road structures are limiting in some ways, and must be taken into account. However it would be easy to do something like close off a lane on the Sydney Harbour Bridge and transfer it to bikes. That would light a fire I am sure.

Although it seems positive here in Melbourne, I can assure you we have to fight for every single metre. In Darebin on Tyler St we just put in a contraflow lane, which is great local infrastructure. But it stops 30 metres short of High St (the main connector) because of three carparks which “could not” be removed. So you either take a detour or ride illegally on the footpath.

Sydney is the worst it’s ever been for cyclists. The draconian new cycling laws, accompanied by hostile media and shock jocks, seem to have given everyone carte blanche to abuse and harass cyclists.

I never thought anything would make me give up cycling but I am so weary of having people hurl abuse at me for “not having a licence” or “not paying tax,” which I do on my car as I am required but not on my bike as no-one asks me to. People now seem to think they have the right to do an inspection on my attire, riding position, bell, helmet and the fact I’m on a cycle path and make a derogatory comment accordingly. My partner recently stopped to let a gentleman cross a pedestrian crossing and was absolutely screamed at, out of the blue. When he tried to reason with him, the man started yelling into the light on his helmet which he apparently presumed was a camera.

Meanwhile a woman in Newcastle reported being stopped by the police for not wearing her helmet while WALKING her bike. And the officer did a repeat around the block to check up on her.

We are no longer allowed to use commonsense to keep ourselves safe by, for instance, jumping onto a wide and deserted footpath to avoid cycling in heavy traffic or we risk a huge penalty.

The new fines make it appear that cycling is a dangerous activity when, generally speaking, it is not. It keeps people healthy and communities connected. It frees up parking spaces and roads. I have been shocked by the NSW government’s new legislation. Although they claim it was done with consultation, in truth they took little notice of what was said during that process. They certainly didn’t consult with health minister Susan Ley who has just spent $10 million trying to get more young women doing physical activity such as cycling.

Having lived and cycled to work in both cities I can tell you a couple of good reasons why Melbourne is far easier to ride in – it’s flat and it’s mostly much cooler. Sydney is humid and hilly and you arrive at work sweaty, Nevertheless I totally agree about the lack of seperated bike lanes, lack of political will (apart from City of Sydney) and slightly more aggressive drivers. I have never understood why the State Govt is so unsupportive of cycling. I think the Alan Jones and Ray Hadleys and their aged audiences have something to do with the negativity. The Baird govt should be doing much much more to promote safe cycling for so many reasons that will benefit them – healthier people and environment. What could be bad about that?

Perhaps Brian Dixon’s rollout of bikeways over 30 yrs ago was more than incremental. Hia contribution seems under acknowledged sometimes.

I ask that Clover Moore’s support for cycling infrastructure has been crucial in Sydney.

But Clover is so detested by the Liberals and the right generally that cycling and bike lanes have been damned by association up here. That toxic rag the Daily Tele has as a result been campaigning against cycling for years; ant council who wants to spend money on bike lanes is likely to cop a spray from the Murdoch media.

Hence Baird’s anti-cycling laws, a cheap way of currying favour with the Murdoch press.

Women also get harassed by drivers who think it’s

very funny to tailgate you or blast the horn. they think its funny: it places your life at risk

Cities are moving towards olden/cycling age.