A new federally-funded plastic microfactory has opened at the University of NSW, offering an effective way to deal with waste and a good way to educate the community about recycling.

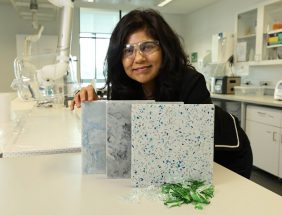

The commercial-scale model developed by the UNSW Centre for Sustainable Materials Research and Technology (SMaRT) can turn discarded plastic into 3D printing filaments and flat products, which can be used in the built environment.

The technology allows industries to build modular recycling solutions which can be scaled up as demand grows.

SMaRT Centre director Professor Veena Sahajwalla says she has already had a lot of interest from local councils regarding the technology.

Lego bricks of a factory

Professor Sahajwalla says building a full microfactory is expensive, ranging up to $1 million, which can prove too costly for local government.

But she says with the new technology, councils can take a modular approach, where one “module” is built at a time.

Unlike a normal microfactory, which can create various types of products from recycled plastic, each module operates under fixed conditions to create a singular product.

“They’re different modules, that’s the big difference,” she told Government News. “They’re all engineered to build different products, which is quite different to what a normal factory would do.”

“It’s a step-by-step modular (approach), kind of thinking about it as the Lego bricks of a factory,” she told Government News. “You can build it up gradually.”

The modules can provide a good starting point for councils to use as education pieces for the community to demonstrate what the technology is capable of, she says.

“It’s still a product that would obviously be useful, and you can still give it away to kids in schools and all of that,” she said. “You can still achieve an outcome, it’s really just going to be in very small units.”

Regional priorities

For councils that are interested in using microrecycling technology, Professor Sahajwalla recommends they start by looking at their own region, to determine what they want to do and what their priorities are.

“Councils can actually think about it in their own context,” she said. “And not just assume that they’ve got to do exactly the same thing as the big council next door.”

The good thing about a microfactory, according to Professir Sahajwalla, is that it can be customised to suit different needs.

“That’s the nice thing about a microfactory, you can actually customise it to meet local requirements,” she says.

Local Government NSW President Linda Scott welcomed the federal funding, but said more is needed to really boost recycling in NSW.

“This type of federal government seed funding is important to help drive innovation and new recycling technology,” she told Government News.

“But much more is needed in NSW if we want to increase recycling and build new markets for recycled products.

“The government needs to work with local councils to deliver regional scale planning for waste and recycling services and infrastructure to help fix our waste and recycling problems and build a circular economy for NSW.”

There are dozens of old government-owned bulk storage facilities dotted along the sides of regional rail lines where these factories could be established at minimal cost. I have been suggesting for ages that these unused buildings, which are massive in size and scale, could be easily adapted to become recycling plants. Their positioning alone on the rail lines makes them ideal for shipping the raw materials in and the finished products out. But it would take the cooperation of all levels of government to get the ball rolling. And it would be ideal to establish these recycling plants in regional areas like the Central West of NSW, where the drought is hurting communities the most. Create these jobs in country towns which really need a boost to their economies. Processing of recyclables would be a big win for places like Trundle, Bogan Gate and Albert which are all situated along an under-utilised branch line which is begging for new freight opportunities to keep the line open. In this way the government would be “killing two birds with one stone” – creating hundreds of new jobs where they are really needed and helping communities suffering from the drought. It would also create many more jobs for the anticipated inflow of new migrants into these areas.