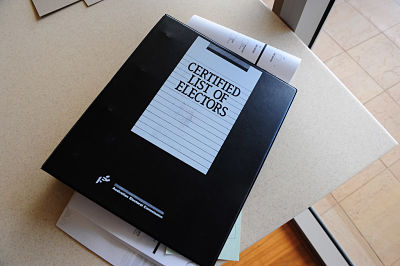

Every working day across Australia, a familiar scene is repeated in state and federal Electoral Commission offices that goes to the very heart of privacy, democracy and data in Australia.

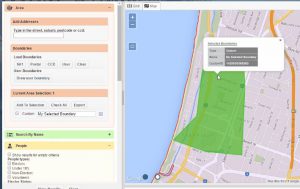

Seated at secure, stand-alone computer terminals, private investigators using just a pen and paper meticulously check the nation’s electoral rolls for details of persons of interest.

It might be a spouse or relative who has unexpectedly disappeared or an executor looking for unknowing beneficiaries of a will. More often than not, it’s debt collectors and their lawyers looking for a physical address to deliver legal paperwork vital to commence proceedings.

No electronic copies of the Electoral Roll information can be made, either by download or mobile device, making manually writing down elector details by hand the sole point of public access.

It’s an obstructive quirk that’s there to stop the mass harvesting of information and protect the privacy of individuals participating in Australia’s compulsory system of secret ballots that underpin our electoral system and democracy.

Yet the Electoral Rolls must be open for access and inspection.

“Under section 90A in the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918, the right to access the electoral roll is integral to the conduct of free and fair elections as it allows participants to verify the openness and accountability of the electoral process,” the Australian Electoral Office says on its official description.

“The AEC also protects personal information on the electoral roll from being misused under the provisions of the Privacy Act 1988,” the Commission adds.

But there’s a catch – and it’s a huge one. The Privacy Act doesn’t extend to politicians or their parties.

While private companies, banks and marketers are all legally barred from electronically accessing or using Electoral Roll information, it’s a very different story for political parties, candidates and their staff who mine, slice and dice voter information using their own proprietary software systems.

And just what voter information is kept on those party and candidate systems, how it is collected and used and what, if any, safeguards are in place to protect it has so far avoided any independent or regulatory scrutiny.

The first rule about party electoral databases is that you don’t talk about party electoral databases.

And with even voters unable to access what is being kept on them, they remain the darkest corner of supposedly open democracy in a digital age.

Privacy Free Zone

When the Australian Law Reform Commission released its landmark review of the Privacy Act in 2008, it delivered a cornerstone recommendation that both major parties were happy to let quietly die through lack of political support.

With a strong sense of the increasing power and potentially intrusive reach of digital technology, the ALRC recommended that the exemption from the reach of Privacy Act for parties, candidates, staffers, contractors and volunteers be dropped.

The move would have opened the secretive and murky way in which data is collected, held and used on electors to independent scrutiny and regulation for the first time.

The ALRC review also suggested that, like with other government and business organisations, individuals should be able to access information held on them by political parties and be able to correct errors in party information holdings.

Specifically, ALRC’s 2008 report said:

“The ALRC is not convinced, however, that all (or even the majority) of information-handling activities undertaken by registered political parties and those engaged in political acts and practices warrant legislative immunity. In particular, registered political parties and those engaging in political acts and practices should:

- collect information by lawful and fair means; ensure the quality and security of the information;

- set out their policies on the management of personal information;

- let individuals know what personal information is held about them; and

- allow individuals the right to access and correct such information.”

The recommendations went nowhere.

[quote]With a legislative amendment needed to cement any new access and oversight regime, both major parties were happy for the change to not even make it past first base.[/quote]

It’s not hard to see why.

Digital campaigns give privacy the finger

With Labor having commandingly won what was then Australia’s first truly web-powered and social media driven election contest – better known as Kevin 07 – data-driven campaigning, targeting and fund raising from voters wasn’t just a new political weapon; it was seen as the must have tactical campaigning advantage.

Since then, both Labor and the Coalition have invested heavily in powerful new analytical, modelling and outreach software that fuses together elector details, demographics, views and concerns and interactions with candidates…and mostly paid for by taxpayers.

So-called “Robo-Calls” and “War Diallers”, political text messages, online advertising, social media targeting and influencer outreach all, in some way or another, rely on party electronic access to electoral rolls because they quite literally tell them where the votes are.

They know where you live, what keeps you up at night and whether or not you’re likely to donate.

But as the party database systems get bigger, more powerful and arguably more intrusive, the secrecy around their operation and holdings intensifies.

Closed window on democracy at work

Because information about electoral databases is so highly guarded, and independent scrutiny completely absent, when information does surface into their operation it’s usually because of a row or an internal dispute.

What is known is that Labor uses a platform derived from its UK cousin known as Campaign Central alongside the longstanding Electrac system. The Liberal Party uses a system named Feedback.

Such is the paucity of information on electoral databases that even the ALRC – the statutory body specifically tasked with reviewing the legitimacy and efficacy of laws – had to reference a 2004 paper by academic Peter van Onselen, now the contributing editor of The Australian newspaper and a former adviser to Tony Abbott during his terms as Workplace Relations minister.

In the paper, van Onselen’s assessment is scathing.

“Compulsory registration to vote coupled with compulsory AEC handover of voter information to political parties is also a violation of individual voters’ privacy. Political party databases storing voter information are excluded from privacy laws which prohibit the retention of such information by private organisations other than political parties,” van Onselen wrote.

“However they are not subject to freedom of information rules either. Until this situation is remedied, political databases will continue to present a threat to key values of the Australian political system.”

And if you’re getting bombarded by unwanted texts and emails from candidates, there’s no stopping that either. Politicians conveniently wrote themselves out of the Spam Act too.

Eroding political trust

If Australian electors are cynical already about the motivations of political messaging and how policy is formed, recent incidents involving both sides of politics and electoral databases won’t do much to restore confidence.

In 2013, three Fairfax journalists – Royce Millar, Nick McKenzie, Ben Schneiders – made an unreserved apology to both the Australian Labor Party and the Victorian Electoral Commission for breaching laws surrounding unauthorised access to electoral data in the course on an investigation into how parties use databases.

Compiled in the run-up to the Victorian state election of 2010 the story, published in The Age, revealed that Labor had “secretly recorded the personal details of tens of thousands of Victorians – including sensitive health and financial information – in a database being accessed by campaign workers ahead of this Saturday’s state election.”

Some of those contacted by The Age journalists expressed dismay at the kind of information being held on them without their permission and the manner in which it was collected.

There are also problems in NSW.

In May this year the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s 7.30 Report reported that former “NSW Labor Party general secretary Jamie Clements had been charged by the New South Wales Electoral Commission for allegedly improperly accessing the state’s electorate roll.”

Labor by no means has a monopoly on controversy over electoral databases.

Federal Western Australian Liberal MP, Dennis Jensen, tipped a bucket on his party’s use of the Feedback database after being dumped as the candidate for the safe seat of Tangney after what he called a dirty tricks and smear campaign that included the release of an unpublished book that allegedly included explicit descriptions.

Among the questions Mr Jensen put to the Liberal Party was whether any third parties other than his staff had access to “confidential constituent information” put into Feedback.

Ringing up the cash

The Liberal’s otherwise inconspicuous Feedback database exploded onto the political stage during the 2016 federal election campaign after a flurry of accusations that the developer selling the software to members for around $2500 a year, Parakeelia, was effectively funnelling parliamentary allowances back to the Liberal Party itself.

For a database so sensitive that its users are reportedly told not to discuss its operation outside the Liberal Party, the sudden spotlight of attention, accusations and questions to Cabinet ministers over sensitive funding details was yet another unwanted headache in an already toxic election campaign.

The raft of accusations and counter claims over party database funding quickly moved to the software used by Labor, which is provided by a company called Magenta Linas, founded by Bob Korbell and Andrew Navakas around 20 years ago.

Headquartered in Melbourne, Magenta Linas certainly doesn’t hide its work with the ALP, or unions on its websites and also lists a raft of other corporate and government clients.

Sometimes it even leaves its dummy drafts up online.

Decade-long row

While Labor leader Bill Shorten stressed that Labor did not ‘own’ Magenta Linas in the way Parakeelia operates for the Liberal Party, the reality is that bitter rows over the public funding of electoral database software funding have been blazing for more than a decade.

So too have allegations over access controls and the potential misuse of elector information.

In 2006, with the Liberals seeking to switch to the then new Feedback systems from a system known as EMS (Electoral Management System) provided by (you guessed it) Parakeelia, recriminations flew hard and fast in the Western Australian Parliament [pdf: the fun starts p10] over access to taxpayer funds to deploy software.

Also in the mix was what access union members working helping out on Labor campaigns would have to elector information.

Then WA Liberal Opposition Leader, Paul Omodei, took aim at Labor over why the ALP’s Electrac system could be funded by the state government but the Liberal’s new Feedback system couldn’t

“The Labor Party developed its own Electrac system and then organised for that to be funded by the state, and the Liberal Party was not given the same benefit,” Omodei roared almost a decade ago.

In 2007, John Howard’s Special Minister of State, Gary Nairn, had another go at Magenta Linas asking the AEC to investigate whether the Australian Council of Trade Unions getting access to Labor’s electroal databases was a breach of the Electoral Act.

The AEC found it wasn’t.

Better systems, bigger risks

Ten years on, successive state and federal governments have changed while the names behind political party software have largely remained the same.

And while the power, reach, holdings and potential intrusiveness of Australia’s electoral software has increased many times over, public and regulatory scrutiny has remained static and inconsequential.

Who, if anyone, will intervene on behalf of Australian voters in the event electoral databases are hacked, or revealed to have been hacked is, is difficult to say.

And there’s certainly little or no political interest in exposing that data to sunlight or the oversight of the Privacy Act.

Leave a Reply