Concrete is the biggest source of construction sector-related carbon emissions, but researchers are working to make the crucial building material more environmentally friendly. And they say governments need to lead by embracing the new generation of ‘green concrete’.

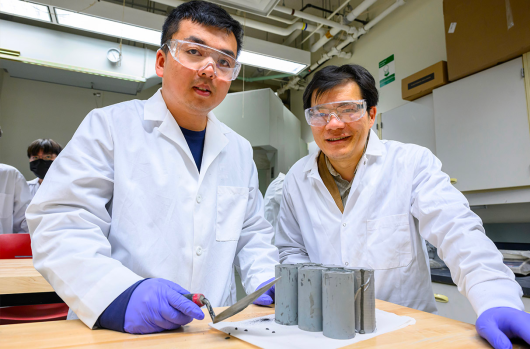

Professor Ali Abbas and a team from Sydney University’s Waste Transformation Research Hub have created a carbon-capturing concrete pavement made with recycled waste, and is about to trial it in collaboration with a Sydney council.

Dr Ezgi Kaya is a structural engineer with development consultants Hatch, which works with clients to identify projects where green concrete can be used.

Professor Abbas and Dr Kaya share a common vision of eco-concrete as the future.

Why eco-concrete?

The high levels of C02 that concrete manufacture produces is linked to the production of cement, the binder that sets and hardens concrete, Dr Kaya says.

If cement and other materials used in concrete can be replaced by recycled materials, the result is a much more environmentally friendly product.

“Cement production is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, so reducing the amount of cement needed is one of the most important steps towards reducing the carbon footprint of concrete,” she says.

“Unlike conventional concrete, which requires a considerable amount of energy and resources to produce, green concrete often uses recycled materials and minimises the use of general purpose cement, a major contributor to carbon emissions.”

Cement replacements can include ash from coal fired power stations – a resource Australia has abundant stockpiles of – and recycled glass.

Recycled glass can be used in the place of sand, which reduces the need to extract sand from rivers causing environmental degradation.

Researchers are also experimenting with ways of adding carbon to concrete blends in a process known as concrete carbon capture.

An emissions reduction driver

Dr Kaya argues that green concrete can be a key driver in reducing Australia’s emissions.

In a review prepared for Hatch, Dr Kaya says concrete is the second most consumed material after water and the biggest contributor to the construction industry’s carbon footprint, contributing eight per cent of the world’s carbon emissions.

Cement production is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, so reducing the amount of cement needed is one of the most important steps towards reducing the carbon footprint of concrete.

Dr Ezgi Kaya

She estimates that carbon emissions can be reduced by up to 80 per cent by using green cement.

“Replacing just 50 per cent of traditional concrete with green concrete could reduce Australia’s carbon emissions by approximately 17 million tonnes annually,” she says.

Local government trial

Late in 2020 Professor Abbas and his team created a carbon dioxide-loaded cement pavement made from coal ash, ground glass and gaseous carbon dioxide and trialled it on a Sydney University campus.

He told Government News the team is currently working on a new trial with a group of Sydney councils, with an eco-concrete pavement to be installed soon in a local government area in the eastern suburbs.

“We installed the first trial pavement two and a half years ago,” he said. “It is standing very nicely, very strong, no cracks – a really good strong performance. Even the look of it is much more appealing than normal pavement.

“We’ve learnt a lot from those trials and they’ve told us that the blend that we have innovated is actually quite well suited for these horizontal infrastructures such as pavements, roadways and cycleways.”

Discussions on commercialisation are underway, and it’s hoped the product will be on the market in the next six to twelve months.

Dr Abbas has also received grants to explore capturing carbon from gaseous waste streams and locking it into concrete.

“Hopefully we’ll be able to create a technology that can take any C02 stream from any industry and blend it with this concrete process,” he says.

Global research

Research into eco-concrete is also underway around the world.

In the US, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology recently reported in the the journal PNAS Nexus that adding baking powder (sodium bicarbonate) could help reduce emissions from the conventional concrete manufacturing processes without altering the mechanical properties of concrete.

And at Washington State University, another team infused regular cement with biochar, a type of charcoal made from organic waste, that had been strengthened with concrete wastewater.

Reporting in the journal Materials Letters, the team said the research could significantly reduce carbon emissions in the concrete industry.

Pros and cons

According to Hatch’s Green Concrete Review, the use of eco-concrete is increasing. It’s already been used in 60 projects in Australia as well as buildings such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi and Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport.

However despite the environmental benefits of green concrete, it does have drawbacks which have acted as barriers to its use, and which researchers are working to overcome.

Eco-concrete is more expensive to produce than traditional concrete, and increasing the proportion of replacement cement materials can dilute strength.

There is a big stewardship exercise here, a big responsibility on the procurement side to bring in and use these sustainable concretes as much as possible to replace traditional concretes

Professor Ali Abbas

But Dr Kaya says the product also offers benefits beyond emissions reductions.

She says it’s more durable than traditional concrete, more fire resistant and has high early age strength, as well as less shrinkage and less cracking. It also has better insulation properties than traditional concrete.

“Its use in construction can lead to more sustainable and resilient infrastructure that is better equipped to withstand the impacts of climate change,” she says.

Dr Kaya says while eco-concrete is more expensive to produce than regular concrete, it requires less maintenance and repair in the long run.

She estimates that the cost impact of using green concrete in a structure is “almost negligible” adding up to 1.4 per cent of the total installation cost compared with traditional concrete.

Dr Abbas says his team has been creating higher strength concrete and has been able to create one that’s almost double the strength of normal cement concrete.

“By incorporating waste into the concrete it allows you to have better environmental metrics, but you lose strength as a trade off,” he says.

“What we’ve been able to do is optimise that for a high strength recipe.”

Stewardship

Dr Abbas says eco-concrete is becoming widely available, with many products already on the market and and the big concrete manufacturers offering a range of lines.

“Cement is one of those versatile products and because of its properties it will continue to be a very useful product for infrastructure development going forward,” he says.

“The question is, how can we make it more sustainable? How can we create longer lasting infrastructure, that we can maintain for longer periods of time?”

As a procurers of construction materials, and builders of infrastructure, Professor Abbas says governments at all levels have a key role to play in showing leadership.

“There is a big stewardship exercise here, a big responsibility on the procurement side to bring in and use these sustainable concretes as much as possible to replace traditional concretes,” he says.

“The good news is we’re already seeing a lot of that.”

Leave a Reply